I used to teach two philosophy courses, a course on Ancient philosophy titled “How to live well,” and a course on Modern philosophy I called “How to be human.” Because each of them only met once a week, they were 3 hours long. I can certainly talk for 3 hours, but classes are much better as a conversation, and their energy would begin to flag part way through.

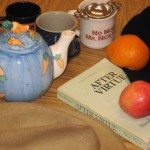

At this point we would break for tea.

Sometimes, I had cookies, but generally I would just buy a variety of apples at the local farm stand–they go quite well with tea. After the tea, they would have more energy (though often less concentration), and the conversation would assume a more relaxed, mellow character of give and take and exploration.

Sometimes, I had cookies, but generally I would just buy a variety of apples at the local farm stand–they go quite well with tea. After the tea, they would have more energy (though often less concentration), and the conversation would assume a more relaxed, mellow character of give and take and exploration.

Many of my students have made tea a regular part of their lives, which I find gratifying. A higher proportion of boys in their 20s own teapots thanks to me, which means they have learned something important about being human and living well.

Why tea?

There are many rituals that involve meeting around a table and sharing food. Some are more time consuming, but sharing a pot of tea can be done fairly simply, and instantly involves sitting together and interacting. It is something that is made, so it involves a little bit of an individual touch, and  a personal touch. The host has a position of control, but also must assume a servant role as he or she serves the tea, asking about milk, sugar, cookies, etc. One already has some small talk asking and answering these questions. Tea is a caffeinated beverage, but generally doesn’t signal the need for intense stimulation that coffee does, leaving instead a more gentle, thoughtful visit (don’t’ get me wrong; I love coffee, too).

a personal touch. The host has a position of control, but also must assume a servant role as he or she serves the tea, asking about milk, sugar, cookies, etc. One already has some small talk asking and answering these questions. Tea is a caffeinated beverage, but generally doesn’t signal the need for intense stimulation that coffee does, leaving instead a more gentle, thoughtful visit (don’t’ get me wrong; I love coffee, too).

It is civilized, and civilizing.

There is also the ritual of preparing the tea, which, like most rituals, can be relaxing and meditative itself. Cold water in the kettle, the wait for the boil, pouring hot water in the tea pot to warm it up, and then offering it up as a cleansing votive offering. Measuring out a teaspoon of tea leaves for each guest, and an extra one in case Mousey or Wode Toad come to visit. Adding in the hot water (it should have boiled, but should not be boiling), and allowing the tea to steep–I would say at least 3 minutes, since I like strong tea, but you should experiment: too soon is too weak, too late becomes bitter, or acquires a tinny, unpleasant edge.

There is also the ritual of preparing the tea, which, like most rituals, can be relaxing and meditative itself. Cold water in the kettle, the wait for the boil, pouring hot water in the tea pot to warm it up, and then offering it up as a cleansing votive offering. Measuring out a teaspoon of tea leaves for each guest, and an extra one in case Mousey or Wode Toad come to visit. Adding in the hot water (it should have boiled, but should not be boiling), and allowing the tea to steep–I would say at least 3 minutes, since I like strong tea, but you should experiment: too soon is too weak, too late becomes bitter, or acquires a tinny, unpleasant edge.

At this point, the variety begins: with milk? poured in before the tea? (try it, it tastes different) sugar? one lump or two? rock sugar? honey? a bit of jelly in the tea to sweeten it? lemon?

Would you like something with that?

Tea is part of what we want to be. Yes, we want to be classy, like the British upper-crust of the 19th century, but sharing tea makes us–or allows us–to do things that make us better. We automatically become more polite–in part because of the atmosphere it creates, but also because of all the interaction:

“Would you like sugar?”

“Would you like sugar?”

“Yes, please.”

“Milk?”

“No, thank you.”

“Here you go…”

“Thank you.”

“You’re welcome.”

More than that, it is shared. It involves the gentle gift of hospitality, and the gracious gift of appreciation. It involves a sensual pleasure that is shared–although it is one which is appropriate and can be talked about in public. Most of all, it moves at a slower pace than doing shots of Jägermeister. It is tea time; it is taken at its own speed, sitting and relaxing.

Sensual joy, physical sustenance, engaging in little comforting rituals, giving, receiving, and sharing hospitality, slowing down in order to have a conversation, listening, being polite–perhaps even witty–most of all, taking the time to sit down and engage with another human being–these and more are the elements that go into tea.

Isn’t that really what being human and living well are about?