The interns and I were talking about Plato’s dialogue Charmides in the afternoon during prep, and then on through tea (apparently, some of them don’t appreciate muffins that leave a warm after burn on your tongue. I, however, thought they went perfectly with today’s post).

Here is my paraphrase of the first part dialogue (Plato’s, not the interns):

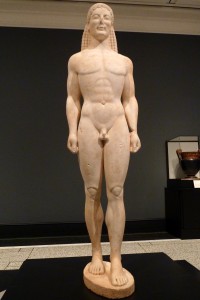

Socrates is chatting up Charmides, a handsome, athletic, sweet-natured young man with good manners and a great personality. Charmides is known for having all the virtues a young man should have, especially temperance, so Socrates asks him to explain what that is.

(Editor’s note: the Greek word here is σωφροσύνης, pronounced soph-ro-sun-ace, and involves self-control. We could translate it prudence, but temperance–in the sense of tempering one’s desires and passions–works best, even though I have rarely heard that word used that way since the beginning of the 20th century.)

(Editor’s note: the Greek word here is σωφροσύνης, pronounced soph-ro-sun-ace, and involves self-control. We could translate it prudence, but temperance–in the sense of tempering one’s desires and passions–works best, even though I have rarely heard that word used that way since the beginning of the 20th century.)

The young man says it’s like being quiet, or not being too fast.

Socrates points out in how many situations being quiet or slow is actually bad– in  classes, the quiet and slow students are not the best, with musicians, the quiet hesitant ones aren’t the best, those who can play loud and fast are generally the best. Do you want your memory to be slow and quiet? Your wit? Your ability to solve problems? No–swift and active.

classes, the quiet and slow students are not the best, with musicians, the quiet hesitant ones aren’t the best, those who can play loud and fast are generally the best. Do you want your memory to be slow and quiet? Your wit? Your ability to solve problems? No–swift and active.

I might add how many times I haven’t been informed of something until it was too late because somebody was quiet or slow. (“Oh, sorry. I meant to tell you that burner was on.” “You know, there is a tool we got in last week that would have made that easier.” “Didn’t somebody tell you we don’t have to save those anymore?”)

The poor young man says maybe it’s like modesty or meekness.

This won’t do: Homer says that meekness is of no value to the man in need, after all, if you are modest and meek, you won’t be able to speak up for yourself, which would be bad, and certainly a virtue like temperance would be good and not bad?

![]() Personally, I only value modesty for people who have much to be modest about.

Personally, I only value modesty for people who have much to be modest about.

As Wode Toad says: “Modesty is the opiate of the mediocre.”

The young man suggests he heard somebody say it was minding your own business.

Well, says Socrates, if everybody just minded their own business, the plumber would never come to your house, that would be meddling, physicians wouldn’t concern themselves with your body, but would only mind their own, folks couldn’t cook for others, or make clothes for others–it sounds like a pretty chaotic community, doesn’t it?

I might quote Marley: “Business!” cried the Ghost, wringing its hands again

“Mankind was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The deals of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

Now, what struck me this time through the story, was how familiar the youth Charmides’ account of this virtue was. Not that young men today are prone to temperance, but it sounds like a  certain model of what might be called “feminine virtues,” or “acting like a lady,” or “biblical womanhood,” or some other cheap brand name. Be Quiet. Be modest. Mind your own business.

certain model of what might be called “feminine virtues,” or “acting like a lady,” or “biblical womanhood,” or some other cheap brand name. Be Quiet. Be modest. Mind your own business.

Even girls who don’t have any of these things overtly said to them, have the practices of being feminine–or, by contrast, not being seen as a pushy broad, or a bitch, a tomboy, or (gasp!) a lesbian–conditioned into them. Don’t be too loud, don’t run and jerk around so, will you sit still?, stop putting yourself out there, let others talk first, don’t be so demanding, don’t be so proud, mind your own business–all of these are part of being nice, and we all want to be nice, don’t we?

I keep expecting one year to have a woman in my classes who is not aware of these expectations, especially since I get a lot of athletes, but all of them are aware of them, and of how often they have failed to live up to them.

Boys get the nice stuff a little, but women of all ages are taught to wear it like a heavy flak-jacket.

Why?

In an age of speed and communication, why do we want to tell half the population they should be slow and quiet? Why would we want to tell young people to be quiet? How much do we lose by that?

In an age of loud voices, why are we telling so many bright, insightful voices they should be meek and modest? If they cannot speak up for themselves, who will? Even more, if things need to be said, they should be said, even if they are critical–especially if they are critical and we don’t want to hear them; that makes any culture stronger.

Commerce, of course, blurs the lines of minding one’s own business, but so does minding animals or children, cleaning up a creek, asking somebody how they are doing and really wanting to know, keeping an eye on the neighborhood, improving the world, showing compassion, fixing flats, and so much else.

I once told my daughter that she comes from a long line of strong-willed women and a long line of men who somehow got a kick out of strong-willed women.

I once told my daughter that she comes from a long line of strong-willed women and a long line of men who somehow got a kick out of strong-willed women.

Now, my grandmother and her sisters would never want to be thought of as loud-mouthed broads–they were all proper ladies (I just wanted a catchy headline). I do, however, owe a big chunk of my notion of what a woman should be like through them, the Thomas sisters. They were all out-spoken, and that was one of the things that made them so wonderful. My grandma was demure and directed the church choir, but she could also command a crew to make thousands of hoagies in one morning a few times a year as a fund-raiser. They could all be deferential, but I would have hated to have run up against them when someone was treated unjustly–they were outspoken; they were forces of nature beautiful and terrible to behold.

Most of all, men or women, why do we make virtue about what we don’t do?

Shouldn’t it be about what we do?