Last week, I was serving drinks at the Bistro bar when someone asked: “Where do you go when there is nowhere left to go?”

It is a question I have been asking myself for over a year now. “Maybe it’s the time of year, or maybe it’s the time of man,” or maybe it’s the time of life in which I find myself, but there seem to be more walls and fewer horizons in my life than there used to be.

One option, of course, is to try to retrace, to try to go back to a time when there seemed to be endless possibilities—or, at least, there still seemed to be possibilities, or to try to recapture that person you once where, and then try to look for new directions, either new possibilities that might have been forgotten or over-looked, or new insights from rediscovering your earlier self.

It is not a bad start, and it may clear your head, but—informative as the past might be—the past is past. As Thomas Wolfe famously pointed out, “you can’t go home again.”

The past is a lovely place to visit, but a person has to find another place to live.

Another alternative is resignation, to choose to embrace the present, to look beyond the problems and limitations that seem to haunt you, and even the numbing dead-ends and losses of your professional and personal life, and to lose yourself in the moment, such as it is, one way or another.

Of course, you can deaden the present, and find solace and comfort where you can, looking for your own personal safe havens or clean, well-lighted places. This may avoid the problem, but it still leaves you with a slow, shuffling specter of yourself to live with.

Heidegger once said that without any real hope of progress, all that remained for the thinker was to prepare a place, a clearing, for the return of god. By and large, this seems to be the last philosophical suicide by an old man whose philosophical acuity had died decades earlier, not having survived his personal integrity by long. Are we worth saving if only a god can safe us?

However, passively resigning to fate and minimizing the desires of the self which connect us to this world is, for many, a viable strategy. This has been part of the rich heritage of Buddhism: to not gorge yourselves upon this world and your own self until you become trapped and wallowing like a fattened banana-fish. Accept the illusion of selfhood, and transcend it.

While it may be selfish to desire things, and it may be selfish to build up oneself—or even build protective walls around oneself—at the expense of others, it is not selfish to demand to have one’s own self, and perhaps even a place of one’s own. To be is to be myself; my own pain is not an illusion to be overcome, but is a part of me. My scars are my skin, and my skin is my scars, and I am both.

Another similar alternative is to seek comfort in the close company of others, to lose oneself either in the warm embrace of friends, or of family, or of other communities. This may diminish the discomfort, or may make it more bearable, but the heart resists and the mind wanders.

To be companions is more than just sitting and breaking bread—it is to be on a journey together, and this needs motions and change, destruction and growth, and perhaps even loss. However, to move is to live; Allons-y!

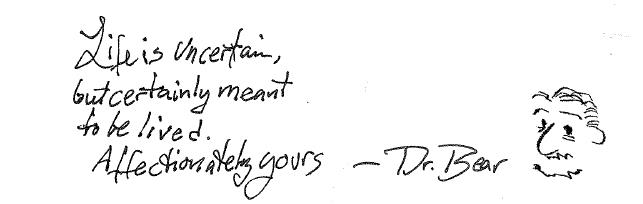

A final alternative that remains is re-invention. No, we can’t change the past, and we can change very little about the present, but the future will always be infinite possibility. There are limits to how far you can re-imagine yourself, but those limits are only slightly smaller than your imagination. The world will set limits on us, but the walls will close in on us and crush us eventually, so why not try to scale them? Why not leap?

Rage, rage! Dare! Sound your barbaric YAWP over the roofs of the world! Wear bright yellow! Write new things! Say what you mean! Make cookies with Sriracha, and Scallops with Seitan!

Are you worried about what you will do after you leap?