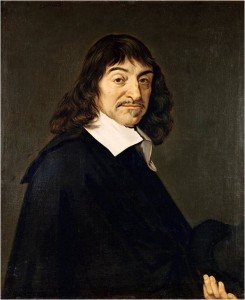

It is one of the marks of a great teacher that he or she equips us to move beyond his or her lessons, even if that means that in the rear-view mirror the teacher’s ideas may seem wrong, misguided, or even foolish. I do not particularly like his philosophy, but I have to acknowledge that René Descartes is that kind of thinker–he changed the landscape of our minds.

It is one of the marks of a great teacher that he or she equips us to move beyond his or her lessons, even if that means that in the rear-view mirror the teacher’s ideas may seem wrong, misguided, or even foolish. I do not particularly like his philosophy, but I have to acknowledge that René Descartes is that kind of thinker–he changed the landscape of our minds.

Let me start with a story:

Imagine the time period around 1619, 1620 or so. A lot of Europe is still medieval–Kings, Knights, Serfs–even the Holy Roman Empire (as either Voltaire or my Mom quipped: “neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire”). Some parts of Europe are moving beyond that–Empires are grabbing land across the Atlantic, The Renaissance has happened in Italy (and beyond!). Nikolai Kopernik (Copernicus) has already published–posthumously–and Galileo has  published, but then recanted and denied it all in order to avoid becoming posthumous.

published, but then recanted and denied it all in order to avoid becoming posthumous.

Most importantly, Luther attempted to convince the Church to return to its faith, and–inadvertently–started a religious revolution, the Protestant Reformation. With that, with his “Here I stand,” he also challenged the authority of traditions.

This was also the beginning of a long series of religious wars and persecutions and would flow across Europe for the next 100 or more years.

Descartes remained a faithful Catholic, at least nominally, and, as far as we know, sincerely as well. As a young man needing to make his way in the world, looking for adventure, having a good education and a great aptitude towards mathematics–both theoretical and applied–Descartes became a military engineer. Much of his career  here is vague, but he was attached to armies which saw a lot of the most brutal fighting in Europe.

here is vague, but he was attached to armies which saw a lot of the most brutal fighting in Europe.

Most notably, his division was at the Battle of White Mountain in Bohemia, where 4,000 Protestants were killed or wounded.

What we have is a bright, sensitive young man, raised as a good, and slightly idealistic, Christian boy, a well-mannered Frenchman, suddenly slogging across Europe in all kinds of weather, watching a war unfold that started for noble, clear moral reasons, but, as is inevitable, degenerated into the messy brutal thing which war is. He saw men die–of bullets, of artillery, of swords and pikes, of infection and disease. He would have seen villages destroyed, crops burnt or stolen, women raped, children starving.

He came back to the cleaned up salons of Paris, where bright people had effervescent conversations about vital matters, and threw skepticism and doctrine about like toys. He set to writing, looking for the clarity of math and the sciences in a very uncertain world, and trying to salvage certainty.

None of that appears in his writings.

What does appear is a few nights in November of 1619, when Descartes was stuck in a house in Neuburg an der Donau, Germany, sitting by the big stove, thinking and writing. He invented Analytic Geometry, but he also devised a method of logic by which to  ascertain truth. He understood that some of what he knew was either false or unreliable, which made all he knew suspect, and he resolved to test all of his certainties, finding they were all doubtable except one, his own existence. Since he was doubting, there had to be a he who doubted, so he must exist (“I think, therefore I am”). From there he slowly proves his way back to the world, and to God.

ascertain truth. He understood that some of what he knew was either false or unreliable, which made all he knew suspect, and he resolved to test all of his certainties, finding they were all doubtable except one, his own existence. Since he was doubting, there had to be a he who doubted, so he must exist (“I think, therefore I am”). From there he slowly proves his way back to the world, and to God.

All of Cartesianism is fairly involved, but what makes him the “Father of Modern Philosophy,” and one of the first modern thinkers are several things, two of which I’d like to discuss: All truth is subject to proof, rather than simply being accepted from tradition and authority, and the mind and the body are fundamentally different.

To me, it is important to remember that this Copernican shift from tradition and ancient authority to proof and individual conviction was undertaken to defend Descartes’ faith. This shift in philosophy is not an attack upon the Church; it is an attempt to return to certainty after the Church’s failure. Although Medieval Christendom produced some great thinkers, it was hobbled by a corrupt power structure which failed on many levels–one of them the spiritual; the Reformation was a reaction to that failure. The religious wars of the Reformation weakened the “Blessed Assurance” further, so that Humanists like Descartes, Montesquieu, Hobbes or Locke were obliged to look elsewhere.

But finally, Descartes’ contention that the self which thinks, and which can be certain, and which can know, is fundamentally different from the frame that sustains it. Whether  or not we believe this, this remains a fundamental way in which our thinking is cast–that my mind and my self are radically different from these 170 pounds of bone, nerve, muscle and sinew, organs–both my own and borrowed–which I seem to inhabit. We think of our body as something (thing? how can the doctor say thing?) we are in, not something we are. It is a wet machine useful for sustaining the mind and for the mind to use, but the mind is other.

or not we believe this, this remains a fundamental way in which our thinking is cast–that my mind and my self are radically different from these 170 pounds of bone, nerve, muscle and sinew, organs–both my own and borrowed–which I seem to inhabit. We think of our body as something (thing? how can the doctor say thing?) we are in, not something we are. It is a wet machine useful for sustaining the mind and for the mind to use, but the mind is other.

This is unacceptable.

The scars on my skin, flesh, bone and nerve are as much me as memories and dreams. The joy of touch and taste is joy for me–regardless of whether I call it skin or sensation or heart or mind. I am my body, but my body is so much more than a complex machine, just as the universe is so much more than the brass model Galileo built.