What is it that we want more than anything else?

What is it what we work those long hours at jobs for, keep relationships alive for, save for, spend for, climb into the mountains for, drive into the city for, sit and wait for, climb those trees for?

Happiness.

Even the closest rivals for what we might want more than anything else—that 22 year old single malt, that night dancing, that meringue, the sweet heat and tingle of physical pleasure, the intoxicating exhilaration of power, success, money—these are all things we desire in the faith (or the hope) that they will make us happy. But these are all fleeting, and too dependent upon the black and red wheel of fate or upon the whims of others.

Even the closest rivals for what we might want more than anything else—that 22 year old single malt, that night dancing, that meringue, the sweet heat and tingle of physical pleasure, the intoxicating exhilaration of power, success, money—these are all things we desire in the faith (or the hope) that they will make us happy. But these are all fleeting, and too dependent upon the black and red wheel of fate or upon the whims of others.

What we want is happiness and fulfillment.

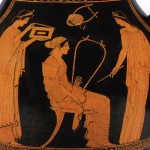

Aristotle argues that happiness is the end towards which all our  human means are ultimately aiming, and that a happy human life is irrevocably tied to what it means to be human. To be a human being is ultimately to be a social being, and a rational being, so any account of human happiness will be an account of the character and types of actions and activities that allow us to find fulfillment—both socially and intellectually. The little ball on that wheel might not land on our number or even our color, and we might be smacked around by an indifferent world and cruel compatriots, but as far as our striving towards human flourishing, towards happiness, towards fulfillment is dependent upon our choices, we can cultivate virtues, excellences of behavior, and of the mind.

human means are ultimately aiming, and that a happy human life is irrevocably tied to what it means to be human. To be a human being is ultimately to be a social being, and a rational being, so any account of human happiness will be an account of the character and types of actions and activities that allow us to find fulfillment—both socially and intellectually. The little ball on that wheel might not land on our number or even our color, and we might be smacked around by an indifferent world and cruel compatriots, but as far as our striving towards human flourishing, towards happiness, towards fulfillment is dependent upon our choices, we can cultivate virtues, excellences of behavior, and of the mind.

That, my friends, is a very concise summary of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics.

I’ve discussed the virtues of character elsewhere, and will again, I’m sure, but this week, I was struck by his discussion of the virtues of the mind. One reason I have tended to breeze through this part is because it is a bit vague, technical, and abstract, but especially because the moral virtues are so much easier to have discussions about. However, the main reason is because I have always associated Aristotle’s account of the importance of the development of the mind in general, and the importance of contemplation and the acquisition of wisdom with Plato’s contemplation of the forms. Aristotle’s account is much richer than that, though.

To be happy, to be fulfilled, to be self-actualized—whatever vocabulary you prefer—one must cultivate the mind, but also exercise it, and in all its dimensions.

He talks of φρόνησις—judgment—how we understand and choose appropriate behavior, the practical decision making of living with others. This is savoir-faire, a kind of knowing, but a way of knowing what to do, and as much a skill as a matter of content knowledge.

I think that the importance of exercising this part of the mind might go without saying—although we might not realize its importance in ourselves, we certainly recognize the lack of it in others—not just crudeness and lack of conscience, but an inability to recognize how are actions can make others happy or ruin their day. Since we no longer live within the confining certainties of Jane Austin’s world, we find ourselves largely playing this one by ear—I know killing is wrong, but when do I send a thank-you note? Even if you do not know the specifics, you can exercise some judgment:

if you do not hold the door for others, you are not a gentleman.

if you are unkind to the wait staff, you are not a good human being.

if you are cruel to children or animals, you are not human.

These are not open to interpretation.

He talks of τέχνη—skill—how we know how to do things. Like most philosophers, Aristotle privileges the abstract over manual labor, but he does recognize that craft and skill are important (he was, after all, a physician, a skill I appreciate). He also recognizes the way in which the knowledge of the hands is a form of knowledge.

To stretch the parts of our minds which create is as pleasurable as stretching our back muscles in the warm sun; to make something good is one of the most fulfilling things a human can do; to make something beautiful is to build ourselves a bit more soul. To not be allowed to make things, to not be able to cultivate skills which we know are ours, to merely process or move things back and forth, or to shuffle papers and figures for a living is deadening.

He talks of ἐπιστήμη—knowledge—and of νοῦς—understanding—both of which are ways we know things. He sometimes makes the distinction of knowledge being about knowing things, whereas understanding being about understanding the abstractions behind them (and wisdom being the understanding the first principles behind everything), but I like to think of them as knowing facts and data—Turkey is in Asia, Sweet Potatoes & Yams are not the same things, the average airspeed velocity of an un-laden European Swallow is roughly 11 meters per second or 24 miles an hour, etc. Understanding can go beyond this raw data and build upon it.

As anti-intellectual as we sometimes can be, the fact remains that we human beings derive pleasure from knowing and from understanding. We want to figure out what that 5 letter word at 8-down is, how to get all 9 numbers in each of the 9 squares, and we want to beat the dweebs on Jeopardy. We do memorize baseball statistics and keep track of basic Tardis data. We try to understand how UT might finally get a winning football team again and how the living dead move. We want to know how Sherlock survived his fall and where the second gunman on November 22nd 1963 was.

Of Aristotle’s fifth intellectual virtue, Σοφία—wisdom, sweet wisdom, holy Sophia, gift of Athena—I have, and will continue to write of her.

Using our minds is a necessary part of human happiness; if we have nothing to think about, we are miserable. Boredom gets us into more trouble than almost anything else.

When I talk to people suffering from losing the ability to discipline their thoughts, they are really suffering. To lose one’s mind is, of course, tragic, but even to lose bits of memory and reasoning is terrifying and terrible.

So exercise your mind—use your judgment, your skills, pick up new information and gain new understandings; not everyone can win at blackjack every time (except, so far, Summer), but you can use your mind, you can control this puzzle-piece of your happiness.

Like this:

Like Loading...

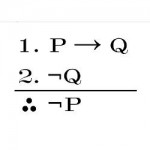

ἢ ὥσπερ Σαπφώ• ὅτι τὸ ἀποθνῄσκειν κακόν• οἱ θεοὶ γὰρ οὕτω κεκρίκασιν• ἀπέθνησκον γὰρ ἄν.

ἢ ὥσπερ Σαπφώ• ὅτι τὸ ἀποθνῄσκειν κακόν• οἱ θεοὶ γὰρ οὕτω κεκρίκασιν• ἀπέθνησκον γὰρ ἄν.