I am a child of autumn; I expect the world to be cool towards me, even chilly, and I am always looking out for the next winter storm. I am not an optimist, nor am I–unless I am really at ease–a touchy feely kind of person. But I do love spring, and I love to be warmed up.

Strangely enough, Maundy Thursday, Green Thursday, the Thursday of Holy Week, the week in the Western Christian year leading up to Easter, was always one of my favorite holidays. This might be mostly for the food, which is featured elsewhere, but is also because so much of the Last Supper distills what is best and most important to the Christian faith. In Germany, Easter in general and Green Thursday in particular is also a celebration of the return of life, of spring, to the world.

The old name—Maundy Thursday—derives from Old French or English corruptions of the first words of the Gospel scripture read at that nights Mass:

Mandatum novum do vobis ut diligatis invicem sicut dilexi vos.

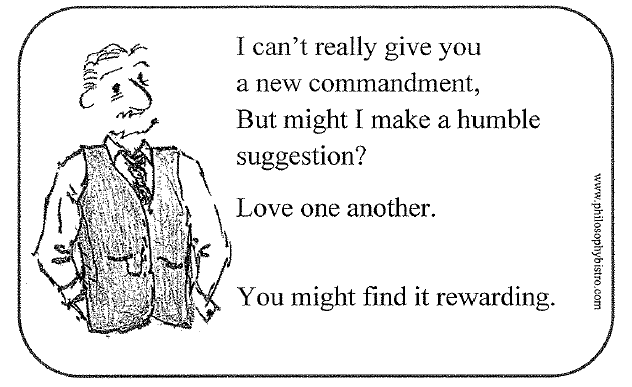

A new commandment I give you, that you love each other as I have loved you.

It commemorates, it celebrates, the culmination of Jesus trying to train his disciples. One more time he tells them to love each other. He tries to reinforce that idea as he washes their feet and shares a meal with them. Love one another. There are legends that the longest living of those disciples, John, at the end of his life, said little more than “Little children, love one another!” The author of one of the Gospels could only summarize his and his master’s life work, his God’s message as Little children, love one another!

But loving is not a new commandment. Earlier in his career, Jesus had taught that all the law could be summarized as Love the Lord with all your heart, mind, etc., and Love your neighbor as yourself. “But who is my neighbor?” you might ask.

When I moved to Nashville, alone and much younger and scared than I could admit to myself, still raw and scarred from my first kidney transplant, it was a strange collection of lesbian and gay neighbors who first ate with me, kept me company and patched me up emotionally. Eventually, my neighbors were a rather strange but true Philosophy department which provided me with a home and great suppers, the staff of an LGBT newspaper I helped with printing and editorial work and with whom I talked almost daily, and the divinity student–deeply religious, yet always trying to act casually about their faith–who inhabited the Disciples Divinity House.

It was a convicted killer who became a good friend and was the best roommate I have ever had; it was a young couple I shared a house with, and lives with, and who taught me how to bake my own bread and honored us by asking us to god-parent their new daughter.

When we moved to Kentucky newly married, it was a wonderful small town congregation that gave us a place to stay and allowed us to be part of their lives. When we had a child, they sent us food—including a whole turkey and a 3-layer pink cake—as well as gentle support and advice. We shared lives with these neighbors, even burying some of them.

In Kentucky, it was also an odd pack of secular humanists at the University who nourished me, providing me with company, support, and even a couch to sleep on in an ice storm.

When I moved back to East Tennessee to wait for my second transplant, it was a quirky little congregation by Buffalo Creek that held me together, sharing a table with us, giving us a place to live and people to talk to. After my transplant, it was also a maintenance and grounds department staffed by North American, Korean, African, Eastern European and Indian seminarians who were neighbors to me.

Now, my literal neighbor is a retired High School coach and Baptist. When I felled a tree across his fence and into his yard, he ran out of his house, and his first concern was: “Are you OK?”

My neighbors are also a fascinating collection of booksellers and barristas who buoy me every day. When the unreality of seeing myself in an antique store sent me spinning, they were the ones I came home to.

Each of these neighbors has come into my life—often not by any choice I made—and has added to that life and made it infinitely richer; at some points, they even made life possible.

Love is a commandment, my Christian friends, but, for all of us, let me suggest that allowing yourself to love and to be loved is rewarding and enriching.

I don’t know about heaven, my lovely ones, but when I am with you, I am back in a garden.

Peace be with you,

Dr. Bear