As anybody who follows my cooking knows, I am always up for trying something new. I also wonder if, in spite of the biographies on the “About the Bistro” page, some of my readers might be unfamiliar with the staff.

As anybody who follows my cooking knows, I am always up for trying something new. I also wonder if, in spite of the biographies on the “About the Bistro” page, some of my readers might be unfamiliar with the staff.

I thought we might have this week’s feature as a panel discussion.

Recently, Andy—long-time friend of the Bistro—

It seems like the Bistro’s version of the old radio  call-in show line ought to be,“Long-time customer, first time eater.”

call-in show line ought to be,“Long-time customer, first time eater.”

(Or maybe “eater” sounds too weird.“Consumer”?)

The gentleman in question has eaten here before;

if I recall, he had a salad, the peace lentils,

and the corn-cakes. Oh, and a side order of Russian Nihilism,

and Community v. Individualism for desert–with some remarkable cheese.

Anyway…he sent me a note asking “Where should I start with Nietzsche?”

Anyway…he sent me a note asking “Where should I start with Nietzsche?”

The mustache. If I were to start with Nietzsche,

it would be that mustache.

What the bloody hell is that thing all about?

Agreed.

“But if we start there, we may never stop.

It was a legendary and epic ‘stache.”

I think he was asking what he should read first, guys.

I think he was asking what he should read first, guys.

For those of you newer to philosophy, Friederich Nietzsche was a 19th Century German Philosopher. He is best known for attacking many of the commonly held beliefs of Western and Christian culture, such as the notion of their being an absolute truth or absolute right and wrong.

I would recommend starting with Thus Spake Zarathustra, Andy.

Written throughout the summer of 1885, and first published i n 1886

n 1886

as Also sprach Zarathustra: Ein Buch für Alle und Keinen

(although the 4th section was added in later printings),

it is written in a heavily poetic, rather mystical style.

It lays out its ideas using the central character Zarathustra

as the author’s spokesperson. It contains many of

Nietzsche’s central ideas, such as the death of God,

eternal recurrence, the critique of the superficiality of modern man,

the “Übermensch”, self-overcoming, and so forth.

Thank you, Peirce;

Brandon, would you throw him a fish?

Tako Nigiri, if you please.

All we have is canned tuna.

Any sesame wafers left?

We could top it with a dollop of that Kentucky Whisky Aioli,

crumble some of those Sriracha Potato Chips on it…

Cooking is about all Kentucky whisky is fit for…

As Peirce said, the book contains many of Nietzsche’s most important ideas, and they are well presented and dramatic. The most famous idea is the “Übermensch,” usually translated as superman or overman. This is a human who is constantly overcoming or overtaking or exceeding their own limitations, as well as the limitations imposed upon them by societal expectations, religion, and traditional morality. A lot of the fans of Nietzsche–his street cred–is based on this idea of the overhuman who rises above mundane morality.

As Peirce said, the book contains many of Nietzsche’s most important ideas, and they are well presented and dramatic. The most famous idea is the “Übermensch,” usually translated as superman or overman. This is a human who is constantly overcoming or overtaking or exceeding their own limitations, as well as the limitations imposed upon them by societal expectations, religion, and traditional morality. A lot of the fans of Nietzsche–his street cred–is based on this idea of the overhuman who rises above mundane morality.

When I taught college, I generally make students read the section on the madman, which discusses the death of God. One of the things I admire about Nietzsche is that he recognizes that the loss of God will actually have a tremendous cost to our culture. “God is dead! What will we do with the rotting corpse?”

This is maybe the most widespread misunderstandings about Nietzsche.

My dad took a Philosophy class in which the professor had written on the board

the first day the old joke,

“God is dead.” – Nietzsche

“Nietzsche is dead.” – God

In other words, “Suck it, Friedrich.” But it wasn’t Nietzsche’s intent to kill God. He just thought he was already dead, and insisted that we all make arrangements for the funeral.

The writing is poetic, even beautiful, and really fun to read. It is sort of like an ancient epic or holy scriptures.It is aphoristic, so you can read it chapter by chapter, and section by section, and don’t really need to study it.

Zarathustra is not, however, systematic or well argued.

Bloody Hell!

It has less logical structure than Wagner’s Ring Cycle.

Wagner’s Ring Cycle.

That would be an interesting Laundry setting;

I suppose it wouldn’t do for delicates, though.

For something with a bit more analysis, you might move on to the The Birth of Tragedy.

I agree.

Though it’s interesting that in order to move on we need to move back.

The Birth of Tragedy was Nietzsche’s first book, written all the way

back in 1872, when he was still a professor of classical philology in Basel

rather than a syphilis-ridden recluse in the Alps.

Which reminds me: Have you ever noticed how much “syphilis” looks like “Sisyphus”?

(Beware what you push up the mountain. It might roll back down.)

Syphilis or Sisyphus,

either way some poor bugger’s going to lose a rock.

I don’t get it.

You are better off not getting it, Peirce.

All righty, then.

The Birth of Tragedy, originally published as

Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik,

or The Birth of Tragedy out of the Spirit of Music, it is an examination of Classical,

and, more significantly, pre-classical Hellenic culture.

and, more significantly, pre-classical Hellenic culture.

Nietzsche explores the rise of the dramatic tragedies.

He contrasts the Dionysian ideal–one of ecstasy and freedom–to the Apollonian idea–one of control and reason. The original theatrical productions were tied to the ecstatic catharsis of the Dionysian rites,

but as it was fully developed, tragedy retains both elements in balance,

allowing the Greeks to look into the abyss of human suffering and affirm it,

passionately and joyously affirmed the meaning of their own existence.

While it has some commendible points, especially in the move away from the c old, rationalist , ordered thinking he calles “Appollonian,”

old, rationalist , ordered thinking he calles “Appollonian,”

it is an oversimplificaton of Greek religious culture, ignoring the earthy nature of the other Gods–even Priapus or the phallic Herma.

Och! But before I spend the my hours criticizing Nietzsche

too much, I must say that it is a truer critique of that blasted bugger Kant then of Apollo.

You can critique Kant later, Wode,

maybe when he comes in for spring peas in dill later this year.

maybe when he comes in for spring peas in dill later this year.

Yes, Nietzsche is definitely a spokesperson for the Romantics against

the dryness and over-rationalization of the Enlightenment.

Finally, Andy, I would recommend Beyond Good & Evil……

Ah. Beyond Good and Evil was first published in1886 as

Jenseits von Gut und Böse: Vorspiel einer Philosophie der Zukunf t.

t.

It is less poetic than Zarathustra, but still largely a collection of observations

and pronouncements in either paragraphs or even short sayings.

By performing a genealogy—an examination of the origins

and nature of Judeo-Christian morality—

he calls it into question, showing its reliance upon philosophical dogmatism,

and proposing instead a perspectivism. It is a dramatic call to arms

to those who cannot abide living within the controls of slave morality,

advancing an extra-moral wisdom to be shared by those kindred souls

who think ‘beyond good and evil’.

Salut, Vache interrompant.

It also introduces important ideas, like the will to power, and the idea that morality is an invention of the weak to handicap the strong.

It also introduces important ideas, like the will to power, and the idea that morality is an invention of the weak to handicap the strong.

OK, to wrap up, guys—is it weird that we are just guys? I mean, it doesn’t seem very inclusive. Except for Alex, the fantasy IT person, the Bistro only has males of the species….

“A woman is a woma n,

n,

and a man ain’t nothing but a male.

One good thing about him,

He knows how to jive and wail.”

Wait: Who is Alice?

Alex. She is our tech support. You haven’t met her, yet, but will at some point.

The service appointment window I was given was “the Twenty-Teens,

give or take two hours.”

Wrapping up, take two. OK, to wrap up, guys, I think ….

Haud yer wheesht, Skinny Malinky Longlegs!

You haven’t really captured why folks still read and quote Nietzsche 100 years after his death

and 130 years after he stopped writing. Although many of his romantic ideas had been expressed earlier, and even his nihilism had already been floating around for years—Dostoevsky had already critiqued the idea of the superman in Crime & Punishment in 1866, nobody writes the call

to arms against our certainties and complacencies better.

He is the John the Baptist of the absence of values, the John Knox of Post-Modernism.

He is the mustached prophet still preaching to punks, cyber-anarchists, and black clad emo kids.

Fair enough. When I was young and alternative and used safety pins as a fashion accessory, I carried a paperback of Zarathustra in the knee-pocket of my cargoes.

Fair enough. When I was young and alternative and used safety pins as a fashion accessory, I carried a paperback of Zarathustra in the knee-pocket of my cargoes.

He is a wonderful thinker to work through, although you have to be careful not to make him an idol.

Wrapping up, take three. I think we should close by each quoting our favorite Nietzsche quote. Although I really like “but it is the same with man as with the tree. The more he seeks to rise into the height and light, the more vigorously do his roots struggle earthward, downward, into the dark, the deep – into evil.” I think I will go with:

Perhaps I know best why only humans laugh.

Only they suffer so deeply that they had to invent laughter.

This unhappy and melancholy animal is, as is proper, the cheeriest.

That faith makes blessed under certain circumstances, that blessedness does not make of a fixed idea a true idea, that faith moves no mountains but puts mountains where there are none: a quick walk through a madhouse enlightens one sufficiently about this.

of a fixed idea a true idea, that faith moves no mountains but puts mountains where there are none: a quick walk through a madhouse enlightens one sufficiently about this.

So many to choose from, but I will have to go with the chapter titles from Ecce Homo, which include “Why I am So Wise”, “Why I Write Such Good Books”, and my favorite: “Why I am a Destiny.” Whenever I do something breathtakingly dumb, I like to say, “This is why I am a destiny.” Oh stupidity, where is thy sting?

So many to choose from, but I will have to go with the chapter titles from Ecce Homo, which include “Why I am So Wise”, “Why I Write Such Good Books”, and my favorite: “Why I am a Destiny.” Whenever I do something breathtakingly dumb, I like to say, “This is why I am a destiny.” Oh stupidity, where is thy sting?

Without music, life would be a mistake.

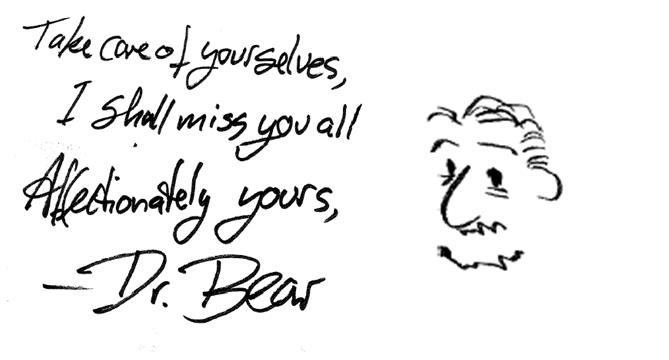

Like this:

Like Loading...

I’ve been thinking about beauty this past week, thanks, in part, to my friend Ben. This is a good time for this, because Tennessee is about to turn its most beautiful, so I am sitting behind an abandoned restaurant, listening to, feeling the spray from, and watching an old fountain, watching the sun play, and thinking about beauty.

I’ve been thinking about beauty this past week, thanks, in part, to my friend Ben. This is a good time for this, because Tennessee is about to turn its most beautiful, so I am sitting behind an abandoned restaurant, listening to, feeling the spray from, and watching an old fountain, watching the sun play, and thinking about beauty. It finds a high expression in Plato, but also owes a great deal to Pythagoras, and, outside of them both, animated ancient art. For these lovers of beauty, beauty is an ideal, a perfection, something we try to capture in art, we aim for in art, and which we cannot find in nature. We have an innate sense of what this ideal beauty would be, and we consider things beautiful to the extent that they come close to reflecting this ideal. This ideal is closely tied to balance and proportion and harmony, and can, in many cases be expressed mathematically. The sculptures of Polykleitos are an example of this; in a pleasing, beautiful face, the distance between the eyes is a set proportion to the face as a whole, and a certain position in the face, and the length of the body, the size of the chest, the width of the hips, the length of the legs…

It finds a high expression in Plato, but also owes a great deal to Pythagoras, and, outside of them both, animated ancient art. For these lovers of beauty, beauty is an ideal, a perfection, something we try to capture in art, we aim for in art, and which we cannot find in nature. We have an innate sense of what this ideal beauty would be, and we consider things beautiful to the extent that they come close to reflecting this ideal. This ideal is closely tied to balance and proportion and harmony, and can, in many cases be expressed mathematically. The sculptures of Polykleitos are an example of this; in a pleasing, beautiful face, the distance between the eyes is a set proportion to the face as a whole, and a certain position in the face, and the length of the body, the size of the chest, the width of the hips, the length of the legs… By contrast to this calm balance of rules, the Romantic view of art aims precisely to tear loose, to suggest power and passion that is not even expressible in conscious thought, let alone within the surgical precision of math. The wild emotion of beauty in art or in nature takes us beyond the calm, placid, everyday, into the cosmos as a whole, the mind of God, or our own subconscious.

By contrast to this calm balance of rules, the Romantic view of art aims precisely to tear loose, to suggest power and passion that is not even expressible in conscious thought, let alone within the surgical precision of math. The wild emotion of beauty in art or in nature takes us beyond the calm, placid, everyday, into the cosmos as a whole, the mind of God, or our own subconscious.