Category Archives: Books

Shout Out!

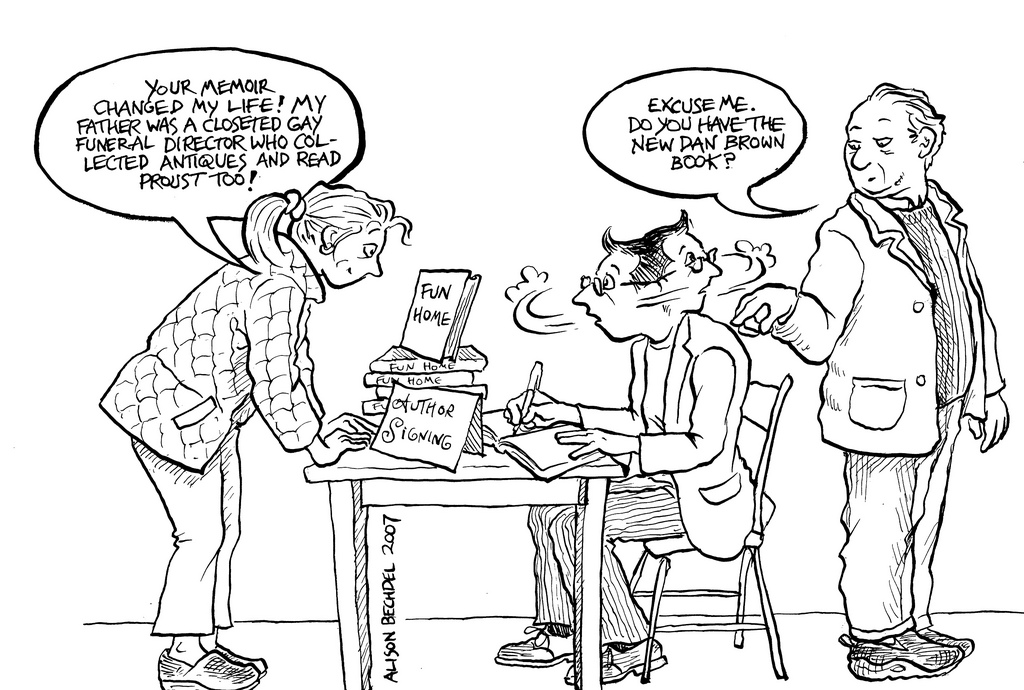

I found out today that a graphic novelist I have long admired won a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship.

I discovered Alison Bechdel’s strip “Dykes to Watch Out For” some time in the 80’s. I think it might have been in one of the papers I read, or the paper DARE, which I sometimes helped with. I loved the witty but real storytelling; the sarcastic but wounded characters. It was sort of like Friends, but with human beings instead of characters. They were each unique, but also reminded me of some of my friends I was hanging out with at the time.

However, I was blown away by the drawings–simple, clean, but very expressive, very real. Mellow, not busy, but still full of life. If I could get back to cartooning, that is the way I wish I could draw.

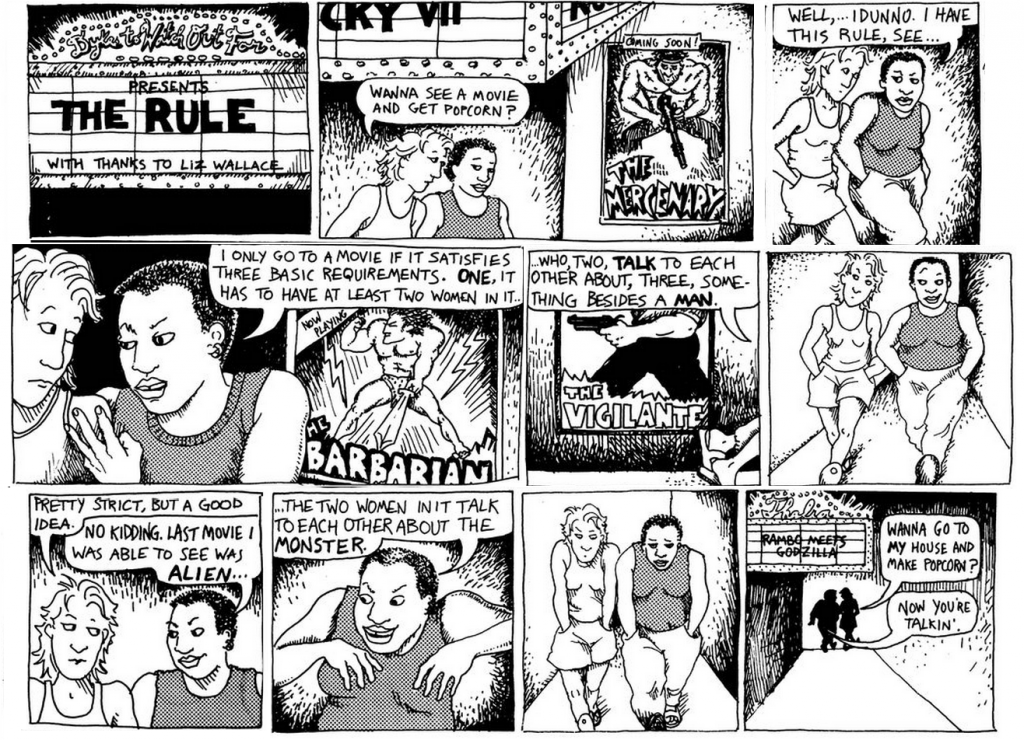

She is also known for the Bechdel Rule, to show how male dominated the film industry is. THE RULE is that:

A movie should have 3 things:

1. At least 2 women,

2. who talk to each other,

3. about something besides a man.

It really is startling how few movies meet those basic criteria.

Ms. Bechdel put the regular strip up on blocks a few years back, to work on longer pieces. She has published two graphic biographies, Fun Home, about her childhood and her father–being adapted as a musical, and Are you my Mother? She is working on a third, The Secret to Superhuman Strength.

Her simple but direct depiction of everyday lives shows how powerful and beautiful a kind of literature graphic novels can be.

We now return you to whatever pop drivel graphic universe you were in.

Tuesday night Question: Reading & Dreaming

Happy 450th, dear Bard.

I watched The Shakespeare Code (DWS03E02) last night, but tonight I am going to try for The Hollow Crown.

Goodnight.

Status

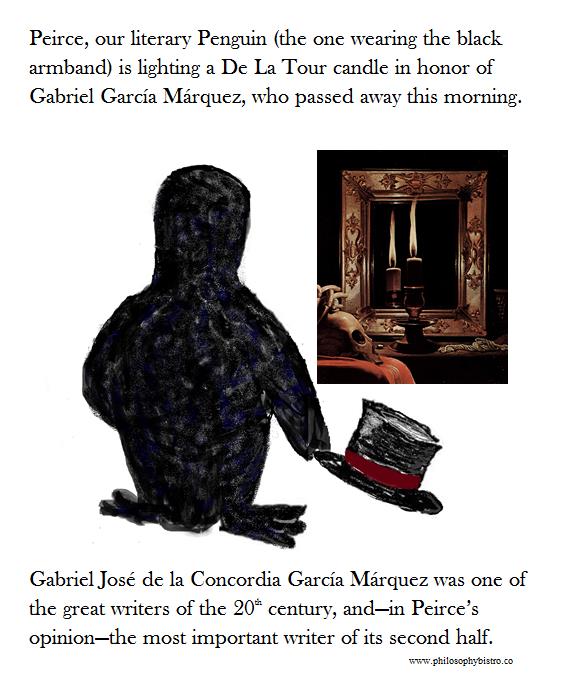

In honour of Gabriel García Márquez, who passed on this morning.

In honour of Gabriel García Márquez, who passed on this morning.

It amazes me how writing can be new, fresh, exotic and strange, and yet at the same time feel ancient and familiar.

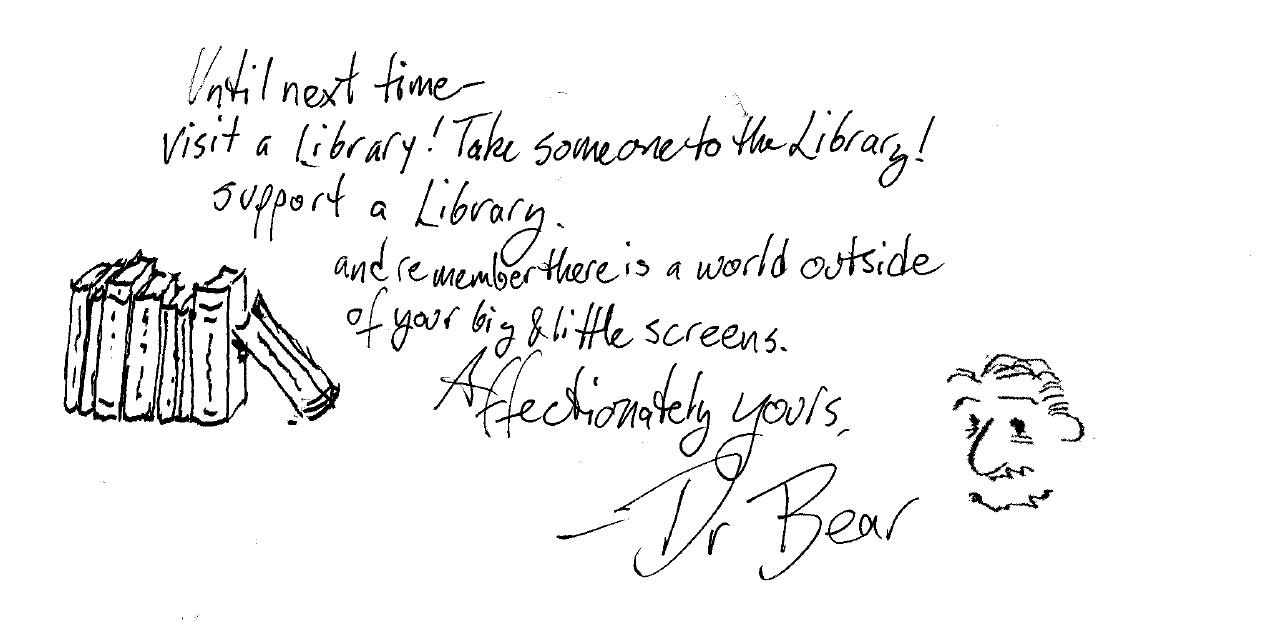

The Once and Future Library

Do you remember the feeling of your first library?

To be surrounded by so many books was like suddenly  being allowed into Aladdin’s cave: so many treasures that they seemed limitless. Then as now, I always want to take more than I could possibly read in those two weeks. Then as now, I am drawn to them–even more than I am to bookstores; they are not home, but they are a haven. Although my parents had quite a good library, I was always reading, and always had a few books checked out, as well as a few on my list.

being allowed into Aladdin’s cave: so many treasures that they seemed limitless. Then as now, I always want to take more than I could possibly read in those two weeks. Then as now, I am drawn to them–even more than I am to bookstores; they are not home, but they are a haven. Although my parents had quite a good library, I was always reading, and always had a few books checked out, as well as a few on my list.

I remember taking my own daughter to libraries and us staying there for hours. There was a  stillness and sunshine, but also amazing librarians–helpful, kind, and bookish. At first, Grace came for the excitement of the public story-time, but soon she came for the books. She would lose herself for hours on some beanbag or chair or table. We each felt a magic to walking down the stacks–those rows and rows of shelves, all housing dazzling wonders.

stillness and sunshine, but also amazing librarians–helpful, kind, and bookish. At first, Grace came for the excitement of the public story-time, but soon she came for the books. She would lose herself for hours on some beanbag or chair or table. We each felt a magic to walking down the stacks–those rows and rows of shelves, all housing dazzling wonders. In the book Inkheart, by Cornelia Funke, the bookbinder Mo has told his daughter: “Books have to be heavy because the whole world’s inside them.

In the book Inkheart, by Cornelia Funke, the bookbinder Mo has told his daughter: “Books have to be heavy because the whole world’s inside them.

My whole family has always felt the same way; to walk down those shelves is to travel across multiverses.

One of our great pleasures in Europe was to see that libraries  were still going strong there as well, as we could see when there was a half acre of bicycles parked by one in Munich.

were still going strong there as well, as we could see when there was a half acre of bicycles parked by one in Munich.

Since I have spent 13 years of my life working in bookstores and only a year or so in a library (I was a OCLC monographs cataloguer rather than a librarian who dealt with the public), I do think of myself as more of a bookseller–pirate to the librarians’ ninjas. However, I do adore them, my librarians, and am grateful to them.

Happy National Library Month, you wonderful, lovely, crazy bunch.

The book industry is going through a tremendous upheaval.

Books are certainly not dead, but they are changing, and their role in our lives is changing. Does this mean the end of libraries?

Don’t be silly.

People will always want books, in fact, people will always need books.

One of the great services libraries have provided is that they have brought books to huge numbers of people, many of whom might not  have had any chance of reading them otherwise. Three centuries ago, few houses had more than one or two books, and many had none. Two centuries ago, only the rich had more than a shelf-full. Even a century ago, books were expensive, and many could not afford them, escecially outside of the middle and upper classes. Libraries put books within the reach of almost everyone. Great fiction (or exciting but not so great fiction), could be in anyone’s hands, as could biographies and travelogues of faraway places, science and engineering books, huge dictionaries and medical encyclopedia, as well as things like atlases and maps. President Harry S Truman, who had to support his family and was unable to finish school, is said to have educated himself by reading most of the Hannibal, Missouri, Public Library. The steel

have had any chance of reading them otherwise. Three centuries ago, few houses had more than one or two books, and many had none. Two centuries ago, only the rich had more than a shelf-full. Even a century ago, books were expensive, and many could not afford them, escecially outside of the middle and upper classes. Libraries put books within the reach of almost everyone. Great fiction (or exciting but not so great fiction), could be in anyone’s hands, as could biographies and travelogues of faraway places, science and engineering books, huge dictionaries and medical encyclopedia, as well as things like atlases and maps. President Harry S Truman, who had to support his family and was unable to finish school, is said to have educated himself by reading most of the Hannibal, Missouri, Public Library. The steel  magnate Andrew Carnegie endowed 2,509 libraries–including another one of my libraries, the public Library in Lincoln, Illinois)–in part because he felt they provided an opportunity for the “working man” to better himself. For years, they were a place anybody could learn, as well as an important public space in most American communities.

magnate Andrew Carnegie endowed 2,509 libraries–including another one of my libraries, the public Library in Lincoln, Illinois)–in part because he felt they provided an opportunity for the “working man” to better himself. For years, they were a place anybody could learn, as well as an important public space in most American communities.

This continues.

This continues in large part because of the way libraries and librarians have approached the problem. They are adapting–not always perfectly, not always smoothly, but they are adapting. The see what the new needs are, and work to meet them where they are. Precisely those things that are changing the world of books are making libraries more important.

This continues in large part because of the way libraries and librarians have approached the problem. They are adapting–not always perfectly, not always smoothly, but they are adapting. The see what the new needs are, and work to meet them where they are. Precisely those things that are changing the world of books are making libraries more important.

It makes me furious when I hear someone describe the internet and e-books as accessible or convenient or free.

They are not.

Neither are they democratic.

Nothing that requires a hundred dollar piece of equipment–and most nooks, kindles, smartphones, etc. are more than that, while genuine laptops and iPhones or iPads can be much, much more–is free. Nothing that requires a service contract to provide internet access, WiFi or data packages is free.

In addition to this, nothing that costs this much is convenient or accessible for citizens of modest means (“Oh honey, mine aren’t just modest; they’re downright meek–shy to the point of agoraphobic”). These folks, who are becoming more and more common in this “New Normal,” are still finding resources at their local public libraries (since students in higher education are also of timid means, these necessary resources continue to be offered to them–even fought for–by college and university libraries).

or accessible for citizens of modest means (“Oh honey, mine aren’t just modest; they’re downright meek–shy to the point of agoraphobic”). These folks, who are becoming more and more common in this “New Normal,” are still finding resources at their local public libraries (since students in higher education are also of timid means, these necessary resources continue to be offered to them–even fought for–by college and university libraries).

I am not talking about the homeless–although the book gods know how much they use the libraries–I am talking about hard-working people trying to carve out a decent life by holding down 2 or 3 part-time jobs.

In addition to still providing books, an amazing way that libraries have adapted is to provided computer and internet access,  as well as some printing. I chatted with one of my local librarians–4 blocks from the Bistro, and although they don’t keep records of use, their 30+ terminals are all in use several times each day, often with people waiting.

as well as some printing. I chatted with one of my local librarians–4 blocks from the Bistro, and although they don’t keep records of use, their 30+ terminals are all in use several times each day, often with people waiting.

This is important.

All those government websites that make information “more” available require internet access. Many of those applications for Medicare or Veterans’ benefits require internet access. Most job applications are now made “easier” by requiring internet access. In an age of “instant” communication, that communication is only accessible to those with internet access.

Public libraries provide that, not just to the margins of our society, but to its foundation, as well as to the foundation of our future.

Libraries have also stepped into the electronic world by lending e-books and freegal, making those more accessible to folks with computers and e-readers, especially to those who cannot make the trip to the library–due to lack of mobility or of transportation.

Of course, all of us–those of modest means, those of the crunched middle means, and even those of comfortable means–can still take our children, our nieces and nephews, or grandchildren to wander down those magic aisles curiously–looking to be fed on words.

Celebrate National Library Month, and hug a librarian.

On second thought, they are book-people; thank them from a distance of at least 3 feet.

Tuesday Night Question:

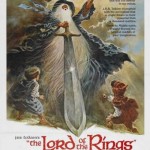

The Book was Better

Looking at the marquees, it seems like almost all of the movies now playing are adaptations of books.

This seems odd since “it is a truth universally acknowledged” that the movie is never as good as the book.

Everybody has a horror story or two of a book or story they love that then becomes something hideous on screen—King fans can fill books with critiques of bad adaptations. For me, the worst adaptation ever will remain the animated version of The Lord of the Rings, released in 1978. Just thinking about it makes me cringe.

Everybody has a horror story or two of a book or story they love that then becomes something hideous on screen—King fans can fill books with critiques of bad adaptations. For me, the worst adaptation ever will remain the animated version of The Lord of the Rings, released in 1978. Just thinking about it makes me cringe.

(On a related note, the DVD of The Hobbit; The Desolation of Smaug was released this week. If you were concerned that the movie was too brief or didn’t add enough material in, it includes a director’s cut.)

Now there are exceptions to the rule about bad movies.

The Grapes of Wrath is an amazing movie in every way, and quite true to the book; nevertheless, the epic novel is better. Similarly (and more recently) The Book Thief was a quite good adaptation, and the acting was masterful; again, though, the book is even better.

So why is the change of medium such a muddle?

Why is the book almost always better than the film?

A lot of it is, of course, the abysmally poor writing–or lack thereof–in the film industry today, but I think the difference goes even deeper.

Some of it has to do with the power of words to tell stories.

We think in storytelling. This is not poetic hyperbole; we think in stories,  and organize information within a narrative framework. Stories go back as far as humans do; they are an integral part of being human. Stories are the most basic way of learning complex, not immediately present information. Our own experiences are integrated into stories so we can make sense of them and remember them.

and organize information within a narrative framework. Stories go back as far as humans do; they are an integral part of being human. Stories are the most basic way of learning complex, not immediately present information. Our own experiences are integrated into stories so we can make sense of them and remember them.

The world is a story we tell ourselves.

So it is not surprising that it seems natural for a storyteller to create worlds for us: beautiful worlds, complex and real, terrifying and moving worlds, worlds more real than the pale things pinging upon our senses.

Now, I do love films, and I do think we can make stories with pictures. We have since we lived in caves. However storytelling is the action and art of words—not sensation that has to be edited into experience, or experience that has to be interpreted into ideas and words, but rather sensation and experience already put into the form our mind would live with.

…and live within.

I love a quick, intense 2 hour encounter with the wonder of cinematic story,

but I can live years inside the world of a book, even on a single, rainy afternoon.

Tuesday Night Play Along: Why is the movie better?

The Old Year’s Books

I met an interesting man over New Years—it’s one of my hobbies, collecting interesting people.

Ben & I were discussing our love of books, how wonderful it is to read and how hard it is to write, and he said something that struck me. He is having trouble with wearing out books—the books he uses a lot, especially the reference books. I thought about how I can wear out books—actually, I can wear out just about anything, but there are books I have read so much that they did begin to wear.

Ben & I were discussing our love of books, how wonderful it is to read and how hard it is to write, and he said something that struck me. He is having trouble with wearing out books—the books he uses a lot, especially the reference books. I thought about how I can wear out books—actually, I can wear out just about anything, but there are books I have read so much that they did begin to wear.

There are books I have worn out, and there are also books that I will eventually wear out.

I have a friend who is quite nice and very kind, but who never reads a book  more than once. I feel that this is like choosing to never see a sunset twice, or never listening to Beethoven’s 7th or Jump, Jive & Wail again, or never returning to New York City, or never eating a chocolate torte with a rich ganache because you have already had one.

more than once. I feel that this is like choosing to never see a sunset twice, or never listening to Beethoven’s 7th or Jump, Jive & Wail again, or never returning to New York City, or never eating a chocolate torte with a rich ganache because you have already had one.

My favorite book of this past year, one that I even bought trade-cloth, new, and retail, because I wanted to own it, was The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wicker.

The premise is slightly fantastical, perhaps even slightly magic realist: a golem and a jinni meet up in the tenements of New York at the tail end of the 19th century.

For those of you who are not immersed in Eastern European Jewish Folk-lore, or students of Kabbala, or fans of the 1915 silent film, the Golem is a creature made of clay who can be brought to life by rabbis who practice Kabbalist rites by using one of the sacred names of God. The Golem is bound to serve a master, and is usually created in a time of great need to destroy the enemies of God’s people.

Most of you should know that a Jinni or a Djin (الجني) is a Middle-Eastern fire spirit, generally with magical powers, and often mercurial and chaotic.

A rather disagreeable man pays a mysterious and dangerous hermit a great deal of money to create a golem who is a perfect wife, then tries to emigrate to the United States. She, as yet un-awakened, is packed in a shipping crate. One night, suffering from a bad fever and from curiosity, he awakens her, but dies shortly after that. She has been created to serve a master—in fact, she can sense the desires of others and feels a strong, even painful, need to help them—but she is now on her own. In the harbor, she jumps out of the ship and walks ashore, into the Jewish section of Manhattan.

Before she gets into too much trouble—she steals a doughnut a young boy desires and gives it to him, but begins to feel a great rage when she is attacked—she is found by a kindly old rabbi who takes her in and tries to teach her how to be human (as well as keep the law).

Meanwhile, a tinsmith in the Little Syria section of New York is repairing a lamp and sets a Jinni free—mostly free; he is free from the lamp, but still captured in human form. To help him hide, the smith tries to teach him how to blend in as a human being. It is difficult, because he is proud and selfish and not used to caring what others think.

Eventually, of course, they will meet.

The characters are vividly drawn, and the plot is well carried out. It is a great story beautifully told, and that is the strength of the book. The time period is evoked in a way that is powerful—the grit and smell of the end of the century in a city that contained worlds of people all speaking in their native tongues.

However, it is also a fascinating meditation on what it means to be human—something each of them has to try to learn. They are also a wonderful study in contrast: she is a servant, and sensitive to the needs of others, solid, a creature of the earth, but underneath, also by nature a killing machine. He is self-centered and proud, living for himself with no thought of helping others, mercurial, a spirit of fire.

Yet learning to appear human changes each of them, and then meeting each other changes each of them forever. In some of the best moments, they meet at night (neither requires sleep, yet neither can move about freely during the day), and find themselves arguing about humans, and especially about her need to connect with and help others, which he finds baffling.

It is an incredible book, so much so that I paid for it.

It is an incredible book, so much so that I paid for it.

If you wish, you can borrow mine—beautiful print on creamy paper edged in indigo—or it came out in paperback this past Tuesday.

For the New Year, eat well, read well, talk well and love well,

and do each as often as you can–