The interns and I are continuing to discuss Greek philosophy, so don’t be surprised if that seeps into a lot of these entrées.

One of the hardest differences to try to make clear between our culture and the ancients–just one little facets of La querelle des Anciens et des Modernes, is how fundamental to their view of the world things like pride and honor and respect were. Since the interns handle money, a lot of my focus is upon ethics.

For most Americans, ethics is almost synonymous with morality, and morality is generally seen in terms of transgressing a set of imperatives. Obviously, the result of transgressing or even failing is guilt.

Socrates, descend from your clouds and talk dirty to us.

Put another way, we think of right and wrong in terms of a code or a bunch of rules. Somewhere in the back of our heads or hearts, we have a series  of “thou shalt not’s” and “don’t even think about it’s,” or our mother’s voice saying: “do you really think that’s a good idea?” We live in a selfish, self-obsessed world, but at the same time are haunted by the voice of a little cricket tsk-tsk-ing us.

of “thou shalt not’s” and “don’t even think about it’s,” or our mother’s voice saying: “do you really think that’s a good idea?” We live in a selfish, self-obsessed world, but at the same time are haunted by the voice of a little cricket tsk-tsk-ing us.

It seems unavoidable that we will break these rules and fail to live up to this code–in fact, it is virtually impossible that we do not. When we do, the result is guilt; in fact, the fear of guilt, the fear of having to walk that long dark hall to face the wrath of Jiminy is what is supposed to keep us in line.

Not that that is always a bad thing: those without guilt are psychopaths, and we do, after all need something to keep us in line, something to avoid descending to chaos and anarchy and cruelty. After all, look how poorly we remain moral with guilt?

Not that that is always a bad thing: those without guilt are psychopaths, and we do, after all need something to keep us in line, something to avoid descending to chaos and anarchy and cruelty. After all, look how poorly we remain moral with guilt?

See, the problem with guilt is that is insatiable–there will always be more to feel guilty about. It is also much better at motivating us to avoid acts than to actually act.

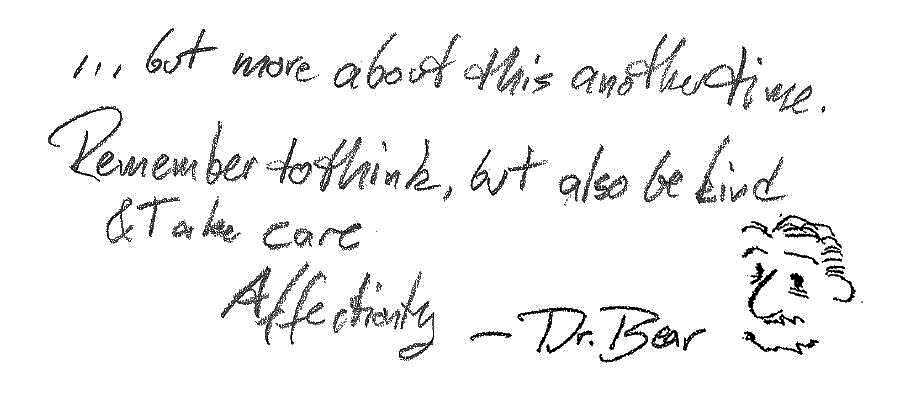

By contrast, honor is an attempt to become better, and to take pride in being better.  It is striving for excellence, and taking joy in both the accomplishment and the striving–like the glory of running fast. It sets goals and standards–virtues and examples–and allows us to construct a narrative of being ethical, instead to just case studies of being unethical. It calls us to act rather than encouraging us to focus upon prevent illicit acts. We shouldn’t be regretting ethical failures–which is what guilt is–but instead we should be cultivating virtues that will allow us to act justly, kindly, honestly, generously, courageously, and so on, in the present and in the future.

It is striving for excellence, and taking joy in both the accomplishment and the striving–like the glory of running fast. It sets goals and standards–virtues and examples–and allows us to construct a narrative of being ethical, instead to just case studies of being unethical. It calls us to act rather than encouraging us to focus upon prevent illicit acts. We shouldn’t be regretting ethical failures–which is what guilt is–but instead we should be cultivating virtues that will allow us to act justly, kindly, honestly, generously, courageously, and so on, in the present and in the future.

And when we do, we should feel the reward of pride in an action well done, and look to the next task to accomplish.

The 300 Spartans at Thermopylae had no reason to feel guilty if they had backed down from the Persians–the Persians did, after all, outnumber them, and the Spartans had fulfilled their obligations to the other Greeks. No, the Spartans defended the fiery gates out of pride; they wanted to perform what they were called to do well.

Guilt prevents the worse from happening, and also nags us to help others, but the cost is an insatiable gnawing self-loathing, and ultimately the problem that the one who can best avoid guilt is the monk in the cell doing nothing.

Pride encourages us to outdo ourselves in living well and doing good, and can see ethics as something to build upon and strive for, but at the cost of encouraging the outward show rather than genuine goodness.

Better than either, though, would be compassion.

Like this:

Like Loading...